The aftermath was surreal. Players involved were suspended a total of 146 games, losing almost $11 million in salary. Five fans were charged with assault, and two were banned from ever attending another Pistons game. It dominated the news cycle and opened up discussions of safety, security, and what happens when very large and physically dominant people are confronted by Average Joes during a game. One of the more interesting discussions since then has come as Stephen Jackson has given interviews about the game and the brawl. His point was that for years players have to deal with verbal abuse from fans who have too much to drink and get rowdy, getting called racial slurs, being told they stink, and hearing things about their families that are cruel to hear. For Stacks, he comments that "every athlete who's ever wanted to punch a fan can live through me." Artest and Jackson went into the stands in response to fans throwing beer cups onto the court at the players, which prompted the response. I'm afraid a lot of carryover from the Malice is happening on social media. And worse, it's happening among the Church. The Malice didn't just cross the line, it leaped over. Fans have always booed, trash talked, and tried to disrupt the visiting team. As well they should. There's a reason they're called fans, it's short for fanatics. Fanatics cheer and boo. But the line comes where it becomes ugly, uncivil, and harmful. That's where I'm afraid we are on social media. We've crossed the line when we engage in lies - One of God's names for Himself in the Bible is Yahweh El' Emeth, God of Truth. Jesus tells us the truth will set us free. As Christians, we are brokers in truth. We're to tell the truth, to let our yes be yes, to not bear false witness, and we have a moral obligation to being honest. When we peddle lies on social media, we're slandering the name of God. We've crossed the line when we lose our civility - Civility is the position we take where we're able to engage others in meaningful conversation, debate, and dialogue about issues. Civility is where we assume the best about each other and we, if the person is a brother or sister in Christ, do not lob hand grenades at their soul. It's easy for a fan in section 300 to scream and throw stuff because there's no threat, and the same thing happens online. We lose civility in both cases because we are functionally rejecting the other's humanity.  We've crossed the line when we major on minors - In a game, pushes and punches happen. In hockey, it's part of the culture! What makes the Malice and other situations like it (Marcus Vick stomping during the bowl game or Myles Garrett swinging his helmet) so troubling is that it takes what should be a minor and becomes a major. Minor things don't need to become major things on social media. Major things need to be major things. We've crossed the line when we lose humility - Humility looks at the Church Universal and recognizes that none of us have a monopoly. Humility follows the example Jesus sets where we're told to consider others before ourselves. Humility in our social media engagement doesn't look like the prideful, boasting, gatekeeper mindset we so often see. Humility holds firmly to what is good, right and true, but it does so with grace. Pride asserts itself and demands to be right at all costs. We've crossed the line when we react, not respond - The Malice was all reaction. In fact, after it all settled down one of the players involved asked his teammates "Do you think we're going to get in trouble?" They reacted. Reaction is visceral, emotional, often times unbound, and sometimes reckless. Responding is careful, measured, and thoughtful. Reaction tends to work like an accelerant, while responding can be an extinguisher. Sadly, too often on social media we react, and we become just like the trolls we roll our eyes at. In Ephesians 4, Paul uses a word over and over again to describe the church united under Christ: One. When we engage with each other on social media, we're not fighting an enemy, we're dealing with a friend, and not just a friend but a family member. Family members don't always get along or agree with one another, but they're marked by love. And that love helps us to keep things in perspective, and to apologize when we've messed up.

0 Comments

Turn on the 6 o'clock news tonight with a stopwatch. Time yourself to see how long it takes before you get discouraged or anxious about the world. My guess is you won't make it to the first commercial break. If it bleeds, it leads. But it doesn't need to bleed for us to realize something is wrong. Stories of fraud, theft, murder, shootings, extortion, crime, sinkholes, and a late season tropical disturbance all can make our blood pressure rise. The reason? Life sucks. Thanks Dan Dewitt for that subtle and profound summary of Genesis 3. And thank you for writing the book Into the Wild to give us a theology of perseverance through a world soaked and crippled by the ripple effect of sin. That ripple effect doesn't just mean we use potty words or look off our classmate's test. It means that everything about our world is deeply and fundamentally flawed and futile. Our cars break down, our crops die, hospitals have morgues, and banks foreclose on our houses. I think the best way to call this is a "Theology of Suck." I know that'll get me in trouble, so please be kind in the comments. When we develop a Theology of Suck, we have to look past, present, and future. Past - We understand the cause of our distress, both cosmic and local. We have a cosmic cause because of Adam's sin. There is, not just a physical but a genetic, imprint of sin. We can't escape it. It's also local because we can look around us at systems, family structures, and more than affect how we live in the wild. Present - We look at what we're going through right now, and we put it in the grid of what it means for God to fulfill His word in Romans 8:28. I've got this as present and not future because we live in the middle of the wild, and we live in the throes of the wild. Our present difficulty, as Christians, is God's perfect plan of sanctification. He can, does, and will bring all things together for our good and His glory. Even when it doesn't feel like it. To that I really commend Chapter 2 and the freedom that can come from Guilt and Shame in Christ.

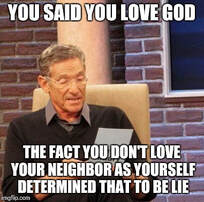

I'm so grateful for my Florida Baptist family. Our statewide meeting was as much a family reunion as it was a business session as it was a mission encouragement. One thing that I cannot shake is a line shared at the Pastor's Conference on Sunday night. You cannot reach who you hate. That shook me. Because I realized it was true. We know what Jesus gave as the "Greatest Commandment" to love the Lord your God with all your heart, soul, mind, and strength. We rightfully plant our flag on that. But we forget that Jesus didn't stop there. He continued, saying the second is like it. It's not really second. It's 1A and 1B. That second command? Love your neighbor as yourself. We might not outwardly or explicitly say we hate some of our neighbors. But what's communicated isn't often what's said. Loving our neighbors doesn't come with a qualification. We're not given an exemption because our neighbor might be an atheist, a Muslim, gay, black, Democrat, Republican, white collar, blue collar, legal or illegal. We aren't given a qualified command. We're given a universal command. Love your neighbor. Our churches are often a reflection of who we love. We generally tend to gather with people who are like us, because we like affinity. We like people who are like us, who think like us, who look like us, who come from similar backgrounds, who share demographic qualities. But our churches often don't reflect our communities. Whether it's ethnic, educational, or something else, the way we reach out often says we only love the neighbors who we're most comfortable with. As pastors, it starts with us. Are we spending time with our neighbors? Are we engaging our communities to get to know those whom God has sent near us? Do we only welcome people into our church who look and smell like us? Do we flinch when we see an interracial couple visiting our services? Or when our neighbor introduces us to his husband do we hide? Loving our neighbors isn't easy - Like I said, we love affinity. Neighbors sometimes are hard to love. They might cuss around us, or dismiss us when we invite them to church, or they might not live the same way we do. And so it's easier to dismiss, ignore, or hide. Jesus never hid from the uncomfortable. He never condoned or approved. But he never ignored. Echo chambers aren't what the church has been called to live in. The church has been called to be salt and light. And that's not easy. Loving our neighbors is an invitation to the Gospel - I think the number one reason God allows us to have a job or to buy a house in an area or be part of the clubs and activities we are is so that we can live on mission. Mission isn't something a vocational missionary does. It's a way of life all Christians are to live out. And we do that when we love our neighbors. It's an invitation to the Gospel because we show that our faith isn't something we just say with our lips, it's something we live out with our lives. Pray for them. Pray with them. Serve them. Take them cookies! Invite them into your home. Get the kids together for play days.  Loving our neighbors we see them as Jesus does - Jesus doesn't see our neighbors in the same categories we do. He sees them as Lost or Found. There's no in between. When we see through Jesus' eyes to see the lostness around us, we shouldn't recoil in fear. We should respond like Jesus did, with compassion. Our neighbors who don't know Jesus are doing what happens when you don't love Jesus. And our ignoring or protesting or condemnation doesn't address the core issue. The core issue is that they are "sheep without a shepherd." They're lost. And they don't need us to scold them for cussing or look the other way when they walk down the street in their hijab. They need us to see them as Jesus does. Loving our neighbors changes how we see our community - Seeing our community changes when we love our neighbors. We begin to look at where we live as an outpost of God's Kingdom, not just the neighborhood we found a good house or a good job. We begin to see the hurts in our community, and we want to know what we can do to fix them. We see the brokenness of family crisis, of economic hardship, of parenting stress, of loneliness in our senior citizens, and more. We don't see houses and cars, we see people who are in God's image and who He loves. And it makes us want to impact our communities because we're truly compelled by love. |

Scott M. DouglasA blog about leadership and the lasting legacy of family ministry. Archives

August 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed